dermatomyositis

Overview

Dermatomyositis (DM), along with polymyositis and inclusion body myositis are classified as a group of inflammatory muscle diseases. While the exact cause remains unknown, dermatomyositis is thought to be an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own muscle tissue. DM classically presents with symmetric, proximal muscle weakness and a characteristic skin findings. DM typically presents in children (juvenile DM) at an average age of 8 or in older adults at an average age of 52. Roughly a third of older adults diagnosed with DM will eventually develop some form of cancer, however, this is not true for juvenile DM. Some patients can have the characteristic skin findings without muscle weakness; this is referred to as amyopathic DM. It is important to establish a diagnosis of DM because the disease is treatable, affects multiple organ systems, and physicians can be more alert to early signs of cancer. Treatment of dermatomyositis requires a prolonged taper of systemic corticosteroids (prednisone); as many as 75% of patients may enter disease free periods without medications within 2-4 years.

DM and polymyositis are relatively rare diseases that occur throughout the world. In adults, both DM and polymyositis affect women two to three times more often than men. Depending on the country, roughly 2 to 9 people per million are diagnosed with DM every year.

DM is believed to result from an immune system process triggered by outside factors such as cancer, drugs, or infections in genetically predisposed individuals. After being exposed to the triggering agent, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own cells in addition to the original trigger. We know that genetics play an important role in developing DM because of identical twin studies -- when one twin develops DM, the other frequently does as well.

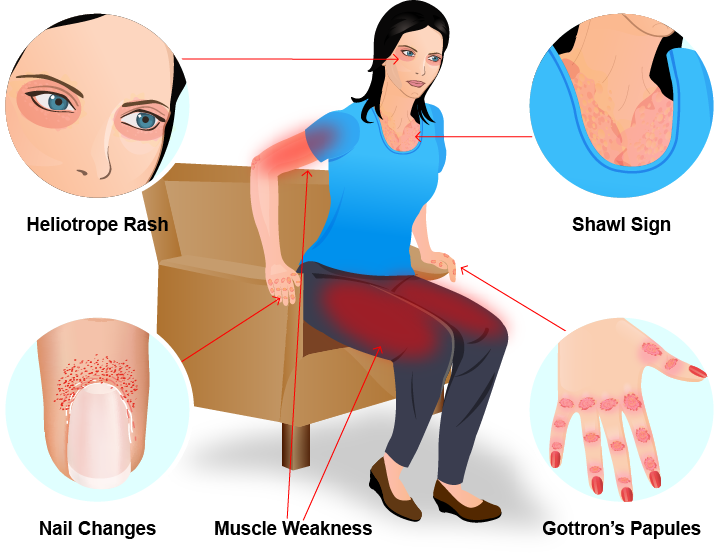

The most important feature in diagnosing DM is the skin finding called poikiloderma. Poikiloderma is a fancy word for areas of the skin that are made up of darker pigment, lighter pigment, and tiny blood vessels that together result in a pink/violet appearance. Poikiloderma is typically present along sun exposed areas such as the “V” of the chest and upper back. This is commonly referred to as the “shawl sign”. Nail cuticles can often look ragged with the appearance of tiny blood vessels.

DM lesions are also distributed around the eyes (the heliotrope sign), knuckles and elbows; however these findings may be subtle. There can also be assoicated swelling around the eyes and face. When lesions are present on the knuckles they are referred to as Gottron’s papules. When present on the elbows, this is known as Gottron’s sign. These skin lesions may itch which can significantly affect patients’ quality of life. Dermatologists will often look for signs of other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, or lupus because symptoms can sometimes overlap.

Some patients initially present with skin findings with no muscle disease. When following these patients long term, some will never develop muscle weakness (amyopathic dermatomyositis) while others eventually develop full-blown dermatomyositis (with muscle disease).

Shawl Sign

Nail Changes

Heliotrope Sign

Gottron’s Papules

Shawl Sign

Nail Changes

Heliotrope Sign

Gottron’s Papules